Early Gender Prediction

Nub Theory Examples: Early Gender Prediction

Anticipating a baby's gender has captured the imaginations of expecting parents for ages, and countless theories and myths have sprung up around predicting a baby's gender via external means. Many of these are nothing more than science-less superstition, but the Nub Theory is one method that, when done properly, really can be quite reliable. This technique involves determining the sex of the baby at an early scan experience by examining the angle and alignment of the genital tubercle, known as the 'nub'. In this guide you will learn all about Nub Theory examples, the science behind it, examples you can see on real ultrasounds and how accurate it is, helping you to determine your babies gender more accurately than many other prenatal methods.

- What is the Nub Theory?

- How Does Nub Theory Work?

- Nub Theory Boy Examples

- Nub Theory Girl Examples

- When Can Nub Theory Be Used?

- Examples of Nub Theory Predictions: Boy vs. Girl

- The Science Behind Nub Theory

- Accuracy of Nub Theory by Pregnancy Week

- Factors That Affect Nub Theory Accuracy

- Boy vs. Girl: What Makes the Nub Angle Different?

- Other Gender Prediction Methods

- How to Interpret Your Own Ultrasound

- Conclusion

- References

What is the Nub Theory?

The Nub Theory is a way of trying to predict a baby's gender between 11 and 13 weeks of pregnancy, many weeks ahead of when a 20-week ultrasound can tell you your baby's sex. The theory is based on assessing the tilt of the genital tubercle — a tiny undeveloped structure in the fetus that will eventually become either a penis or clitoris. Around 12 weeks, the genital tubercle, or 'nub,' is visible in both male and female fetuses. However, supporters of the Nub Theory say that by closely studying the angle of the nub in relation to the baby's spine, they can determine the gender with great accuracy.

How Does Nub Theory Work?

The basic premise of the Nub Theory is this:

- Boy Prediction: If the nub is angled upwards (at 30 degrees or more from the spine), it suggests the fetus is developing as a boy.

- Girl Prediction: If the nub is angled parallel to the spine or points slightly downwards (less than 30 degrees), the fetus is likely to be a girl.

It's important to note that Nub Theory is not foolproof, and it should be taken with a pinch of curiosity rather than certainty. Many parents-to-be enjoy using this theory as a fun way to speculate about their baby's gender, but it's not meant to replace medical advice or definitive results.

Nub Theory Boy Examples

These nub theory boy examples showcase distinctive features commonly observed in male ultrasound scans between 12-14 weeks. In these images, you'll notice how the genital tubercle (nub) typically points upward at an angle greater than 30 degrees relative to the spine - a key indicator for male gender prediction. Each example is accompanied by detailed explanations to help you identify and understand male nub characteristics.

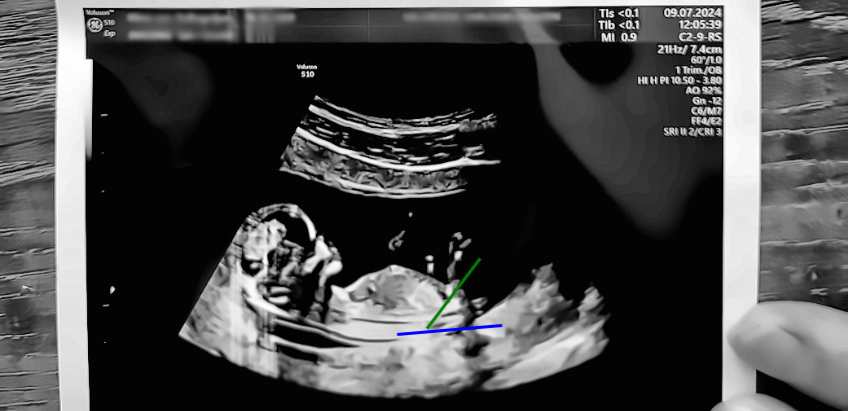

Clear Boy Nub Example - 12 weeks + 3 days

Notice the distinct upward angle of approximately 47 degrees. This is a textbook example of a male nub angle.

Boy Prediction at 13 Weeks

Located in the middle right of the image, the nub shows a clear upward angle exceeding 30 degrees from the spine line. This distinct angle correctly predicted male gender, which was confirmed later in the pregnancy.

Boy Nub Example - 12 Weeks + 5 Days

The nub on the left shows a distinctive upward angle characteristic of male development.

Nub Theory Boy Example - 11 Weeks + 6 Days

While this scan is a bit early at nearly 12 weeks and shows a less distinct angle, it was confirmed to be a boy. Note the clear black circular shape which is the bladder.

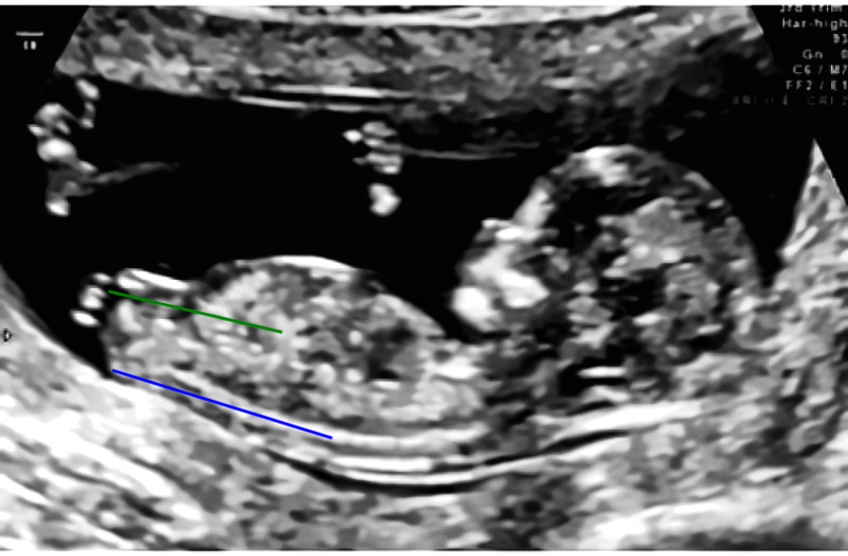

Nub Theory Girl Examples

These nub theory girl examples demonstrate key characteristics typically seen in female ultrasound scans between 12-14 weeks. In these images, you'll notice how the genital tubercle (nub) tends to point parallel or downward relative to the spine - a classic indicator for female gender prediction. Each example includes detailed analysis to help you understand what to look for.

Clear Girl Nub Example - 12 weeks + 4 days

Notice how the nub is almost parallel to the spine, with an angle of less than 10 degrees. This is a classic example of female genital tubercle positioning. For a detailed analysis, refer to the annotated version with measurement lines in the examples below.

Girl Prediction at 13 Weeks

The nub appears to point slightly downward relative to the spine, which is a characteristic sign of female development. This prediction was later confirmed to be correct.

Girl Nub Example - 12 Weeks + 2 Days

In this picture the nub is the white stripe that is having a higher contrast. This is not to be mistaken for the leg that is pointing upwards. The nub is almost parallel with the spine.

Nub Theory Girl Example - 13 Weeks

This scan shows a clear downward-pointing nub relative to the spine, a characteristic feature of female development.

Free Nub Theory Tool

Analyze your 12-14 week ultrasound and get insights into your baby's potential gender with our free guided tool.

When Can Nub Theory Be Used?

The best time to apply Nub Theory is during an ultrasound between 11 and 13 weeks of pregnancy. Before this period, the genital tubercle has not developed enough to be distinguishable, and after this window, the baby's external genitalia start to take a more recognizable form, which could overshadow the nub itself.

Ultrasound technicians will typically take a side profile image of the baby, showing the spine and the nub clearly. This is the best view for making predictions based on Nub Theory.

Examples of Nub Theory Predictions: Boy vs. Girl

Let's dive into some real-life examples to see how Nub Theory can be applied. These examples are based on common scenarios, and any ultrasound images referred to are hypothetical for educational purposes.

Example 1: Boy Nub Theory Prediction

Around 12-13 weeks, an ultrasound technician captures a clear side profile of a fetus. The nub appears to be angled upwards, pointing away from the spine at about 47 degrees. According to Nub Theory, this upward angle suggests the fetus is likely a boy. The higher the angle, the stronger the likelihood of a male prediction.

- Angle: 47 degrees

- Nub Position: Upward (greater than 30 degrees)

- Gender Prediction: Boy

Example 2: Girl Nub Theory Prediction

In another scenario, a 12-week ultrasound shows a fetus with a nub that is nearly parallel to the spine. The nub is not pointing upwards; instead, it lies flat, with a slight downward angle. This configuration suggests the fetus is likely a girl, as the nub has remained low rather than angling upward.

- Angle: Less than 10 degrees (parallel to the spine)

- Nub Position: Parallel (or slightly downward)

- Gender Prediction: Girl

Example 3: Unclear Nub Angle

Sometimes, the nub is not visible on the ultrasound. In the image below, you can see that the nub is not clearly distinguishable. In such cases, it is impossible to apply the Nub Theory accurately. Without a visible nub, the method cannot provide reliable predictions.

- Angle: Unknown

- Nub Position: Not visible

- Gender Prediction: Inconclusive

The Science Behind Nub Theory

While Nub Theory is popular among parents-to-be and even some ultrasound technicians, it's important to recognize that it's not based on solid scientific consensus. The genital tubercle undergoes rapid changes between weeks 11 and 13, and predicting the baby's gender with this method is only an educated guess.

Research into the accuracy of Nub Theory has provided mixed results. Some studies have found accuracy rates of around 75-80%, while others indicate that the method is less reliable, especially in the earlier stages of the 11 to 13-week window.

'The overall success rate of predicting fetal gender in the first trimester was 75%. When excluding those fetuses where a prediction was not made, correct determination increased to 91%.'

Accuracy of Nub Theory by Pregnancy Week

| Gestational age | 11–11+6 weeks | 12–12+6 weeks | 13–13+6 weeks | 14–14+6 weeks | 15–15+6 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender not assigned | 3/24 12.5% | 19/143 13% | 5/38 13% | 0 | 0 |

| Correct male | 3/8 37.5% | 54/78 69% | 16/19 84% | 1/1 100% | 1 100% |

| Incorrect male | 3/8 37.5% | 11/78 14% | 1/19 5% | 0 | 0 |

| Correct female | 10/16 62.5% | 55/64 86% | 15/21 71% | 1/1 100% | 0 |

| Incorrect female | 5/16 31% | 3/64 5% | 2/21 10% | 0 | 0 |

| Total correct when attempted | 13/21 62% | 110/124 89% | 30/33 91% | 2/2 100% | 1 100% |

| Total incorrect when attempted | 8/21 38% | 14/124 11% | 3/33 9% | 0 | 0 |

| Overall correct | 13/24 54% | 110/143 77% | 30/38 79% | 2/2 100% | 1/1 100% |

| Total cases studied | 24 | 143 | 38 | 2 | 1 |

Factors That Affect Nub Theory Accuracy

Several factors can influence the accuracy of a nub-based gender prediction:

- Gestational Age: The later the ultrasound is performed within the 11-13 week window, the more developed the genital tubercle will be, making gender prediction easier and more accurate.

- Ultrasound Quality: High-quality ultrasound machines and skilled technicians increase the likelihood of obtaining a clear and accurate image of the nub and its angle.

- Fetal Position: If the fetus is not positioned in a way that shows the nub clearly, the technician may struggle to get a reliable image for gender prediction.

- Nub Development: In some cases, the nub may not have developed enough to make a clear determination, or the angle may not be as pronounced, leading to uncertain predictions.

Boy vs. Girl: What Makes the Nub Angle Different?

The key to Nub Theory lies in the differences in how male and female genitalia develop from the same starting point. Early in pregnancy, both male and female fetuses have a genital tubercle that looks the same. As the fetus develops, this tubercle starts to differentiate:

- In boys: the genital tubercle begins to angle upwards, eventually forming the penis.

- In girls: the tubercle stays relatively flat or angles slightly downward, forming the clitoris.

By observing these differences in the angle, ultrasound technicians can make early predictions, although the accuracy depends on various factors.

Other Gender Prediction Methods

While Nub Theory is one of the most popular early prediction methods, there are several other ways expectant parents attempt to predict their baby's gender. Some of these include:

- Ramzi Theory: This theory claims to predict gender based on the placement of the placenta on the ultrasound at around 6-8 weeks of pregnancy.

- Skull Theory: Proponents of Skull Theory suggest that the shape of the baby's skull on an ultrasound can indicate gender, with more angular skulls indicating boys and rounder skulls indicating girls.

- Old Wives' Tales: Many fun myths, such as the mother's cravings, heart rate, and morning sickness severity, have been linked to gender prediction. However, these have no scientific basis.

How to Interpret Your Own Ultrasound

- Look for the Spine: Ensure you have a clear side profile of the baby, with the spine visible. The spine will help you gauge the angle of the nub.

- Find the Nub: Look for the genital tubercle, which will appear as a small protrusion between the legs.

- Measure the Angle: Compare the angle of the nub in relation to the spine. If the nub is pointing upwards at 30 degrees or more, it's more likely a boy. If it's parallel or slightly downward, it's likely a girl.

- Take it Lightly: Remember that this is not a definitive method. Many parents enjoy the process of guessing, but be prepared for surprises at the 20-week anatomy scan.

The Nub Theory offers an exciting and early way to speculate about your baby's gender during the first trimester. While it can be a fun and engaging activity, it's important to remember that the predictions made using this method are not always 100% accurate. For those who prefer certainty, it's best to wait for the 20-week anatomy scan or opt for non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for a more reliable answer.

Additionally, you can draw your own lines on your ultrasound for free at nubcheck.com. It's a simple tool that helps you determine the gender of your baby using the Nub Theory. Give it a try and see if you can make your own prediction!

-

Accuracy of sonographic fetal gender determination: predictions made by sonographers during routine obstetric ultrasound scans

Manette Kearin, Dip App Sc (Nursing), BNursing, Grad Dip Ed (primary), DMU, MSc (midwifery), corresponding author; Karen Pollard, ADipDMR, GCertUnivTeach&Learn, MHEd, MEd; and Ian Garbett, BSc, GDipMathematics, MSc